My mind's house has infinite rooms

Centuries ago, a poet named Simonides of Ceos (556-468 B.C.E.) lived in Greece. He was the one responsible for inventing the system of mnemonics that we still use to this day to remember things.

Sometimes mnemonics are a sentence to help you remember spellings. Who misspells the work rhythm frequently? Rhythm Helps Your Two Hips Move—there! Now you'll never misspell this word again because you have a mnemonic.

According to legend, he was called out of a dining hall to speak to two guests whereupon the hall collapsed killing everyone inside. Ordinarily, to remember the guests' names, he associated each person with a particular location in the dining hall. He used this accident as the impetus to develop a memory strategy called the Method of loci.

'Loci', of course, is the Latin word from which we derive the English word 'location', so this is Memory by Location. Nowadays, we use terms like the Memory Journey, Memory Palace, or Mind Palace.

How detailed is your memory?

In English, the mark at the end of this sentence is called a 'full stop' or 'period'. You created that memory sometime around age five. Connected to that is another one about a comma and its function. They certainly share neurons (these are the bits in your brain, much like the bits in a computer memory module) because you learned them at the same time and their functions are closely related.

However, in an entirely different place in your brain is another set of neurons that allow you to identify the appearance and use of a colon and a semicolon. You learned about them at a different time when your brain was ready to accept more complicated thoughts. Still, between the first memory and the second, there is a connection to a third part of your brain for 'punctuation' that ties that and all the other symbols you know together.

It is further tied to Miss Kendal who taught you about full stops and commas, and Mister Richards who explained the use of semicolons. Teachers and punctuation are connected, and all together it is called an associational neural network.

Building a Mind Palace

By exploiting this fact we can create a memory tool, often referred to as the Mind Palace. This requires you to use your imagination to recall a location that you know intimately and then populate it with objects and task reminders so that when you need the information once again, all you have to do is take a metal stroll through your Mind Palace and what you need to remember will be sitting right there, ready for you to use.

Sequencing a list in this way allows you to quickly scoot through this mental image until you find precisely the one you want. By knowing just the first object in your list you trigger your mind to begin remembering all the objects. Similarly, by knowing the last object in the list, you can also go backwards through the list. By remembering the first and last objects, you can get to the needed information faster by starting at either end.

You can even use the same Mind Palace to remember different lists, provided each starts and ends with a different object. On the other hand, you might like to have multiple Mind Palaces for different purposes. You will have to pick what works best for you and your circumstances.

To Begin Construction

First, choose an actual physical location that you know well. If your objective is to remember things for work, then it may be helpful to remember your office or work area.

Create a repeatable pattern, in the order that you ordinarily encounter each location and object. Remember all the locations and then practice looking at them (in your mind) both backwards and forwards. Think of the office door when you arrive at work; the little tree in a planter sitting just inside; the reception desk; your mailbox; the worn spot in the carpet; the coffee machine; the cup rack; the photocopier; the printer; and everything else on the way to your workstation.

Pretty soon you'll have a comprehensive list of locations that you can assign to objects or tasks that you need to recall. Remember the locations in order and assign a number if that helps you. Try to focus on fixed objects that won't get removed, or whose location won't easily change.

A Practical Example

For more general items, such as a shopping list, you might select a favourite walk through a park that you know well. On that walk you remember all of your favourite places, for example, like this:

Now, for each location, place something that you want to remember. Let's try a simple example of a shopping list of bread, tomatoes, cream, coffee, butter, bananas, etc., and you could imagine it like this:

At location ① have a loaf of bread walking into the park—and making it silly looking helps, so give it spindly legs, a walking stick, a top hat, and a monocle. Animated images are best for triggering your memory. The ② newspaper seller could be replaced with a pile of tomatoes trying to sell newspapers with news about tomatoes. At ③ have a bottle of cream nibbling on an acorn. ④ could be a pair of coffee cups having a chat. ⑤ could be someone sliding helplessly along the path covered in butter. ⑥ could be a banana trying to climb the tree…

Keep it silly and keep it animated, and these will make the list more memorable. Slowly you'll discover that remembering more than a dozen items is easy to do. You'll get faster with practice, and you'll develop a quick-list of silly images that you can call upon. You will also develop the ability to make up amusing images more easily.

Do Mind Palaces Really Work?

Yes, indeed they do. These are the tools most often used by memory contest champions. They can recall massive lists of names, dates, faces, events, strings of numbers, word lists, or anything else you can imagine. You could memorise the Periodic Table in this way, if desired.

The major shortcoming of this technique is that it is useful for lists, or for triggers to remember other things. It is probably not going to remind you about how to calculate the volume of a sphere for a test, which is:

sphere volume = 4/3 π r3

There are alternative methods for remembering such things, or if you are so inclined, you can manipulate the Mind Palace model to accomplish this. Here is one example of how you could make it work by being a bit more creative.

Imagine a big glass sphere containing four spiders (letter S) sitting on a clear glass plate above three vipers (letter V) to represent four over three, next to a pie (pi), beside three rats (r) that have been trapped in a glass cube (r3). It's more complex this way, but that image could be in your mathematical Memory Palace, so you always remember that formula. S & V tells you that it is sphere volume which is 4/3 times π times r3

If you're willing to work at it, almost any data can be stored in a Mind Palace. Its strength is lists, but there is room for more complex data.

Why Do We Forget Things?

If your brain is in good condition, you have the capability to remember everything you have ever experienced. There is no 'capacity' problem with an average human brain. All of your experiences are still tucked away inside there and can be recovered with the correct stimulus.

You possess about a billion neurons, each of which can hold a speck of data. Each one of those neurons has connections to roughly 1,000 additional neurons, and each of those neurons has connections to another thousand, some the same ones, and some much further away. That 'first neuron' therefore has nearly unlimited connection possibilities. The more neurons that are involved, the more complex the memory can be.

What appears at first to be a few gigabytes quickly soars to several petabytes of storage (which are millions of gigabytes) in a human brain. If you lived to more than 100 years of age you would not exhaust your storage capacity.

How Our Brains Remember

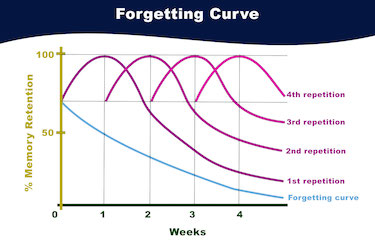

Some of our earliest memories are strongest from getting the most use, grinding a virtual path between neurons that makes something unforgettable. The more you think of something the more resilient it is.

This is the origin of the notion 'Use it or lose it'.

The Takeaway

The most powerful, durable memories are the ones that are not unique; the ones that are closely tied to sounds, smells, tastes, and circumstances. Try asking an older person, alive in the 1930s, 40s, 50s, or even 60s what carbon paper is, and they can recall manual typewriters, and how we made copies of documents before the photocopier was invented, or the computer was common.

They may not have thought of these things for years, but the information is still there, ready to be recalled as soon that the right association neural network is triggered. The Mind Palace is a tool to trigger associations, and it is a highly effective tool. With a little practice, it will work for you, too.

Now…if only you can remember what you've learned here until you get a chance to actually set it up and practice it! Just for fun… What were the six items on the shopping list in the park used in the example?

1. ..... in a top hat, with cane and monocle.

2. ..... selling newspapers about .....

3. ..... eating an acorn.

4. Two cups of ..... chatting.

5. Slipping on a path covered in .....

6. ..... climbing a tree.

Good job. You remembered, and it wasn't even your own Mind Palace!

Read more about other effective memory techniques such as mnemonics, acronyms and chunking.